Vernacular—Richard Simpson in Tar River Poetry

Vernacular—Richard Simpson in Tar River Poetry

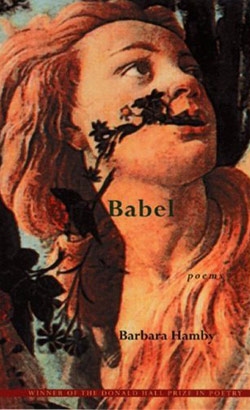

Barbara Hamby’s poems have a jumping verve and forward drive. She knows American life and language with exuberant precision and links them to the popular culture, high art, and languages of many other countries, all of this in a profoundly assured, resourceful, inventive, and unifying voice. Babel is her third book, the first two Delirium, (University of North Texas, 1995) and The Alphabet of Desire (NYU, 1999). Across them she spins out huge sentences with multiple accretions, pools, eddies, backwaters, the propulsive main current almost always coming directly out of conversational speech. Put me anywhere, she seems to say, and my American voice will prevail.

Control of syntax and poetic form are essential to her effects. Lines send tentacles two-thirds or three-fourths of the way across the page, if not longer, and she thinks nothing of making a forty-line poem out of one sentence. With C. K. Williams and many others, she likes to start a first long line at the left margin, the second a tab-space in, repeating the process until the single-stanza poem ends many lines later. Or she’ll use a spacious two-line stanzaic free verse or a related configuration to open things up and let fly. Occasionally she tightens it down; favorite forms are a sonnet-like seven free-verse couplets or, strikingly, thirteen. But many poems occupy two pages or more.

She is reminiscent of Whitman, the Beats, and recent loquacious American poets like Patricia Goedicke and Gerald Stern. Further, her intensely allusive and referential work brings up many earlier writers, notably Shakespeare and the British Romantics, especially Keats. She doesn’t mask her wide reading and gives her diction a handsome sophistication. The final section of her first book, Delirium, is “The Autopsy of John Keats,” a magnificent sequence of monologues by figures around the poet during and after his last month. But her métier is the first-person poem whose speaker seems close to Hamby herself. The usual tone is informal and never far from delighted laughter.

As with other brilliantly comic and voluble American poets like William Trowbridge, the most apposite writer here may well be Byron in Don Juan. Like Byron, Hamby conveys a meditative yet sociable respectfulness enen if a passage or poem is brash, pugnacious. Surly, insolent. She speaks with and for the reader. Even more to the point is Hamby’s quite Byronic use of the vernacular–its self-regarding yet outgoing pleasures, its wacky and delicious catalogs, its interjections and asides and contractions, its vast tonal range. She sees with uncanny exactitude and has ears, as musicians say, that can hear paint drying in Tahiti. Below is the opening half of the single-stanza ubi-sunt “Ode to Hardware Stores,” a poem showing how far she’s willing to take a commitment to American subject matter and loquaciousness:

Where have all the hardware stores gone—dusty, sixty-watt

warrens with wood floors, cracked linoleum,

poured concrete painted blood red? Where are Eppes, Terry Rosa,

Yon’s, Flint—low buildings on South Monroe,

Eighth Avenue, Gaines Street with their scent of paint thinner,

pesticides, plastic hoses coiled like serpents

in a garden paradisal with screws in buckets or bins

against a brick wall with hand-lettered signs

in ball-point pen—Carriage screws, two dozen for fifty cents—

long vicious dry-wall screws, thick wood screws

like peasants digging potatoes in fields, thin elegant trim

screws—New York dames at a backwoods hick

Sunday School picnic. O universal clevis pins, seven holes

in the shank, like the seven deadly sins.

Where are the men—Mr. Franks, Mr. Piggot, Tyrone, Hank,

Ralph—sunburnt with stomachs and no asses,

men who knew the mythology of nails, Zeuses enthroned

on an Olympus of weak coffee, bad haircuts,

and tin cans of galvanized casing nails, sinker nails, brads,

20-penny common nails, duplex head nails, flooring nails

like railroad spikes, finish nails, fence staples, cotter pins,

roofing nails—flat-headed as Floyd Crawford,

who lived next door to you for years but would never say hi

or make eye contact. . . .

As American as all this is, Hamby like many of her contemporaries in this country, set poems abroad (do I detect an entrenched cliché?). France and Italy receive particular attention. Babel’s second section “Thirteen Ways of Looking at Paris,” the epigraph unsurprisingly from Stevens on Blackbirds. But even her most Continental poems are sunk deeply in the rich funk of American speech, and in the best Hamby sails past any talk of hackneyed substance and enthralls the reader. “Brain Radio Harangue” has her saying, “I’m never more American than in another country, / Jerry Lee Lewis chasing me down the Champs-Elysées, . . . / [or I’m] hearing Miles Davis in some restaurant, his horn like a disease / in my blood.” In a seamless weave she’ll talk about people she’s seen on the street in Italy or Tallahassee, what she had for dinner last night at which restaurant in L.A. or the 13th Arrondissement, films she saw at a Hawaiian drive-in years ago, the great Florentine churches and artists, her husband or nephew or mother or father, Camille Claudel or Kristallnacht or deep-American-South backwoods barbecue or California Hot Kung Pow Shrimp, Elvis or (beautifully) “Lester Young’s sidewinding sax,” three versions of Racine’s PhPdre she’s caught in London and Paris, her ’77 Toyota she used to take out onto the I-10 from Florida toward New Orleans–and on and on.

At times one wonders how all this works. Anyone who talks so relentlessly about herself risks immediate banishment to an ice floe. But I have yet to see the first microbe of self-absorption, arrogance, or bombast. Indeed, a risk might come from another direction–from her convivial amiability, which occasionally suggest she’s trying too hard to charm the reader. I suspect she’s aware of the danger. Her books have three sections, and the first in Babel is “The Mockingbird Blues.” Two sectional epigraphs and the first five of the section’s twelve poems have a new acidity, an acrid sharpness, perhaps in response to a concern about too much amiability. The splendid, harrowing epigraphs are from Ecclesiastes (“And you shall rise up at the voice of the bird, and all the daughters of musick shall be brought low”) and from the nightmarish Keats of “Ode to a Nightingale”: “Adieu! The fancy cannot cheat so well / As she is fam’d to do, deceiving elf.” The section stares hypnotically at language itself.

The fifth poem is the sonnet-length “O Deceitful Tongue,” which I cite in full:

Rogue slab in the slaughterhouse of the mouth,

you love all words that whistle like bombs

through the delphinium sky. O tongue that sucks

honey from the vinegar bush—demagogue, street

preacher, cutpurse at the afternoon hanging—break

my neck a thousand times till I remember the digits

of your prime number. Drunk tongue, warling,

malt-mad forger in the bone orchard, give me

your traitor’s code, so I can whistle my psalm

through the sinworm night. Tongue of rough

bread, blues tongue, wolf tongue. Kiss me,

deceitful mouth, smash my curtain of skin, devour

the air wild with bees, swallow their wings,

make me a bloody hive for their bitter queen.

This poem’s compressed figuration, tonal darkness, and dense, distilled musicality take Hamby far from the vernacular, far toward elliptical poets like Donne and Hopkins.

But then Babel returns, in this first section and the rest of the of the book, to a more open syntax and a somewhat more obviously comic tonality, as in “The Mockingbird Invents Writing,” a risible junket through the various weirdnesses of human talk and script. The second and third sections act out an ancient tug-of-war for American writers, the magnetic attraction of Europe set off against a fierce love of the home country. As noted above, the second section is centered in Paris, and the third is called “American Odes,” each poem having “ode” in its title. (The hardware poem comes from this group.” The telling sectional epigraph is from Ginsberg: “It occurs to me I am America. / I’m talking to myself again.” Hamby seems to assert that she can take a rather foreign genre, the ode (Keats and Wordsworth come inevitably to mind), and will at least try to make it inarguably American by the sheer force of her vision and language.

One recalls that the British Romantics themselves did not entirely know what to make of their European antecedents and contemporaries–and that for the Romantics a “solution,” if there was or is one, came from language itself, the triumphant personal music a Charlotte Smith or a Wordsworth or Coleridge discovered in, say, descriptive-meditative blank verse–or even more to the point, the unity Byron found in the narrator’s voice in Don Juan, a poem whose subject matter was aggressively international (including military and cultural wars). In a world where things fly apart or get blown up, the brain and its great achievement, language, may provide at least the promise of unity.

Let me offer a coda. Hamby speaks often of popular music and musicians, and her love of white rock-‘n’-rollers like Elvis and Jerry Lee Lewis is not at all surprising in a writer born in 1952. But for me the musicians most relevant to her way of proceeding are the great jazz players of the bop idiom who came to ascendancy immediately before and after Hamby’s birth year–Gillespie and Parker, Milt Jackson, ultimately Eric Dolphy and the ineffable John Coltrane, with the overarching father-figure the gorgeously exact but tumultuous pianist Art Tatum. No musicians have ever been as authoritatively American, yet these players listened hard to European classical music and drew on its theory and practice. These players let loose torrential fusillades of a million elegant notes. Very like Hamby’s own, their aesthetic was on of long lines and phrases, and just as she does, they created an atmosphere of nonstop expressiveness that seems, at last, infinite. Yet their enormously sophisticated art worked from a structural and emotional basis of popular songs and common forms like the 12-bar blues, and again like Hamby, all of these players could establish their primacy in tight quarters, a sonnet-like sixteen bars here, a sonnet-like 78-rpm three minutes there. Further, all were great ballad players, masters of an intimate reaching out to the listener, yet even in their quietest moments, the torrents were implied. The delightful phrase “bebop babble” occurs in one of Hamby’s earlier books, as if she were seeing up a pun in advance on her latest volume’s title. I smiled when I saw the phrase. She may love Jerry Lee and The Big Bopper, but she’s a bop poet.