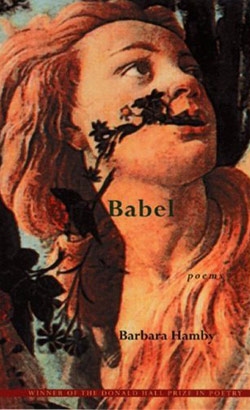

Steve Gehrke in The Missouri Review

“I’m translating the world into mockingbird,” Barbara Hamby’s Babel opens, “into blue jay, / into cat-bombing avian obbligato, because I want / more noise, more bells, more senseless tintinnabulation, / more crow, thunder, squawk, more bird song, / more Beethoven, more philharmonic mash notes to the gods.” The passage not only announces the author’s poetic (or antipoetic?) Intent but provides a preview of the book’s many pleasures to come: the linguistic thrill, the wickedness, the bite, the pounding-its-fist-on-the-table insistence of the voice, the manic intelligence, the humor and an inclusiveness matched among contemporaries only by Ashbery and Albert Goldbarth. Her is a poet, we understand, who will not rein herself in or dumb it down, who insists that poetry can say more by saying more.

This tendency toward expansiveness has been present in Hamby’s work since her fine first book, Delirium, which won both the Norma Farber First Book Award and the Kate Tufts Award. But in Babel, Hamby seems to have broken into a more refined voice, one that is able to mock and praise simultaneously, as when the speaker misses America for its “pill-popping Hungarian goulash of everything.” There’s no question that these are witty poems, often reminiscent of the electric, frenzied hilarity of Robin Williams at his coked-out best, moving easily between reference points, challenging you to keep up. What keeps the long, clause-riddled sentences from slipping off track is the sense that the poet is not simply being encyclopedic but is searching for the authentic among this crush of images, shopping for the sublime in the superstore of an overstimulating world. This search frequently takes the form of a love-seeking, which is simultaneously a search for muse. The poems also search inwardly, as at the end of “The Mockingbird on the Buddha,” when the speaker feels her body break open “like a Spanish Galleon raining gold on the ocean floor,” or in these lines from “The Tawdry Masks of Women”: “when I see myself / in bus windows or store glass, the shock never wears off, / for I recognize myself and see a stranger at the same time.” There’s a surprisingly mournful quality to the poems as well, especially in “13th Arrondissement Blues,” when the speaker’s own moroseness is extended to a collective sense of feeling “naked, / chained by impulses we can hardly control, trying to understand why our hearts are breaking like a ship / off the stony coast of some unknown new world.”

Babel is a challenging book, one that thrusts us into the superconductor of a postmodern mind, that threatens at times to overwhelm us with its abundance of reference points, but that never becomes unclear, never forsakes meaning for the sake of verbal inventiveness. This is not only Hamby’s best book but one that marks, I believe, a major poetic achievement. It’s a book that dazzles and energizes, that challenges and comforts as it celebrates and mourns “our cries of bigger, faster, more, more, more.”