Café Review–Anne Brittings Oleson

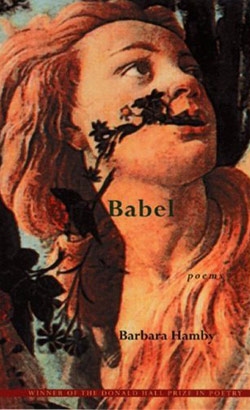

In Genesis Babel is a city in Shinar whose residents were interrupted in their building of a tower tall enough to reach heaven when God confounded them, forcing them to speak different languages. The resulting confusion of words stopped all progress. Barbara Hamby has chosen well in titling her new collection Babel, for the explosion of language—the sheer quantity as well as the sound —is so enormous that nay reader might be stopped in her tracks.

In every poem of the collection, words and images erupt from the poet’s mind onto the page: there simply doesn’t seem to be any way to contain everything Hamby packs into her work. The barrage begins with the opening salvo of “My Translation,” a piece in which the speaker claims to be

translating the world

as if it were a bomb, a thief, a book. Chapter One: the noun

of my mother’s womb, verb of birth, adjective of blood,

screams, fluorescence. Chapter Two: explosions of words

growing into sentences, arms, legs, tentacles.

It’s a brilliant passage about birth, first into life, then into language: a bomb from the womb exploding into words. The fallout from this mushroom cloud covers everything, including the seemingly prosaic subject matter of “Ode on the Potato,” and that of the sardonically mouthwatering “Ode to Barbeque,” which is “hot, oh yeah.”

The most delicious part of Hamby’s poems, though, is the explosion of sound in the mouth of the reader. Such lines as “the id- / id-idiot princess who shares my skull, her skills / resemble nothing more than the damson plum jam / jars (“Babel”) delivers such sibilance and consonance, that the S’s and K’s and M’s all jump joyously from the lips in a tangle of language the residents of Babel could only wish to have heard. Who could resist the seductive sounds of a line in which people “down their drinks quietly, faces sliding to one side” in “Ode on My Sharp Tongue?” Who would not feel beaten and bruised by “the battle cry of the Bible Belt” in “Ode to American English”? Babel is certainly a collection, which confounds with its richness of language and subject matter; yet in Barbara Hamby’s case, this confounding of the reader is a good thing. It is not often one is stopped in her tracks by such abundance, where the play of words and images explodes into so much joy.