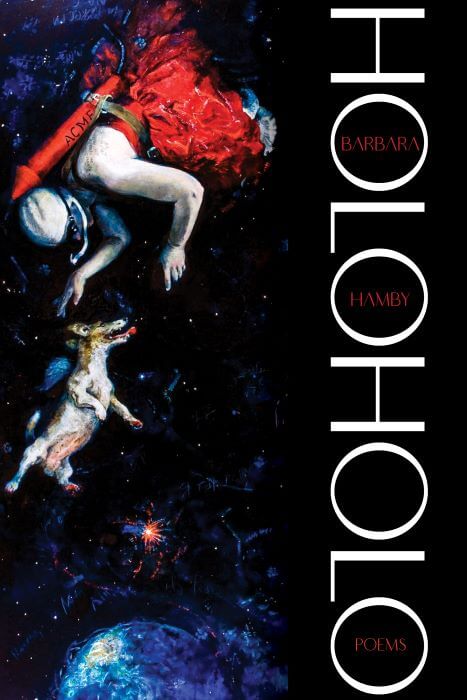

Holoholo, University of Pittsburgh Press

Reviews

A Review of Barbara Hamby’s Holoholo, Reviewed by Risa Denenberg

“Some poems generate physical sensations in my body. When I read Ferlinghetti, for example, I see myself playing hopscotch. With Walt Whitman I sense the cadence of boots strolling through Brooklyn Heights. While reading Holoholo by Barbara Hamby (University of Pittsburgh Press, 2021), I felt the rhythmic to-and-fro movement of a swing combined with the up-and-down movement of a see-saw. I also found that, once I started reading, I couldn’t put the book down. Instead, I carried it with me throughout the house, from kitchen to bathroom to bed, and read its entirety in one long, breathless excursion.

At first, I wondered if I was sufficiently spry to follow the trail of these sprinting odes. How to taste and savor them? I eventually decided to simply enjoy the words—fast and furious—for the sensual joy of their running-brook sounds, their sweet and sour tastes, their reach backwards into the past and leap forward into the future, and their syntactic mastery of the run-on sentence. And once I plunged in, I had no great difficulty running up and down these lines with their titillating language.

The book has three sets of odes: “Americanski Odes,” “Ontological Odes,” and “My Holoholo Odes.” Every poem centers on someone, some place, some moment, some exigency. At times celebratory, these odes are not laudatory, indeed there is much critical thought running through them. Each holds onto a thread of narrative; each poem is a story unto itself, and many stories are picked up, like so many stitches, later in other poems. The treatment of their subject matter is a romp of meanderings that jump from “My Mother’s Lingo,” to a drive “on Venice Boulevard with Emily Dickinson,” to “The Brides of India,” to the “Last Peach of Summer,” and “Those Little Cookies You Dip in Wine.”

The delightful word “holoholo” is an Hawaiian term with an imagistic meaning that sums up the act of wandering about with no intent or purpose. It offers the gamble of leaving the house without keys or wallet and simply letting fate have her way. It’s the sort of word found in many languages that describes a complex mood or tells an entire story; such words are sadly lacking in English. It’s an apt metaphor for Hamby’s writing. In her hands, holoholo seems to mean wandering from thought to thought, idea to idea, image to image.

In endnotes, Hamby tells the reader that she grew up in Hawaii, and “the landscape of the islands and its beautiful lingo are a paradise I keep inside me always.” Regarding odes, she says, “Unlike the elegy … the ode celebrates and contemplates living …” And regarding the enormous reach and landscape of these poems, she says: “I find it thrilling to be part of that 4,000-year conversation between my deepest self and that of human beings who have come before and those who will follow.” An admirable undertaking indeed.

In “Americanski Odes,” we find news, kitsch, musings on parental one-liners (e.g., “See you in the funny papers,” or “I have a bone to pick with you”), surfer slang, the American Diner, laundromats, and “Words for Parties,” including “shindig, bash, / meet-and-greets, raves, blowouts, and barbeques.”

In “Ode On My Prison” we learn about:

a couple arrested

for selling hundreds of tickets to heaven

which they said were made from pure gold

and all you have to do is hand yours over

to St. Peter and you are ushered into paradise. Tito Watts,

the mastermind of this scheme, told the police

Jesus gave him the tickets in the parking lot

behind the KFC and told him to sell them

so he could pay Steve, an alien Tito met at a bar,

to take him to a planet made of drugs.

Meanwhile, the narrator waits,

for something supernatural to appear, not Jesus,

but maybe Walt Whitman walking to New Orleans

with his brother, a cloud of words crowding out Stevie

and the other aliens as Walt fuels his own dream

of America where we’re looking after each other

Two somewhat dissimilar definitions of ontological are “the branch of metaphysics dealing with the nature of being,” and “showing relationships between concepts and categories.” In Hamby’s “Ontological Odes,” there are some of each. She tells us in “Ode to Marivaudage, Ratiocination, and BlahBlahBlah,”—fabulous words, those first two, but I’ll let you look up their definitions—about her love of language, a love that is evident in every poem in Holoholo. There is a delightful combination of high and low diction here, and a reminder of North Florida—where I once lived—in citing the town, “Two Egg.” I imagine anyone reading this book will stumble upon their own nostalgic references—its reach is that wide.

An ontological reference to the nature of being is found in the poem “Ode to My Younger Self,” which is a long tribute to youth—Hamby’s and others’—which starts with the lines I think many readers would nod to,

You were beautiful and stupid though you thought

you were so smart, and in a way you were.

Because you loved poetry and Beethoven and apples

And closes with this venerable self-appraisal,

and The Song of Solomon told you that love could be poetry

so thank you for staying up all night reading and not going

out to bars, and I really appreciate that dance class

you took three days a week all through your thirties,

and after that the yoga. I’m feeling fit right now,

and I know I have you to thank, and those eleven years

as a vegetarian. You really took care of my heart.

In “Ode to the DNA Cocktail (Shake that Baby. Oh Yeah)” is an ontological list of concept and categories, where various alcoholic drinks— “martini,” “Old Fashioned,” “Bud Light,” and “White Russian”—are matched with “your mother’s rage,” “your grandmother’s nose,” “tailgate parties,” or “the novels that shone a light / into the crevices of your mind’s gulag.”

“My Holoholo Odes” travel the globe through time, gazing at “a room of Gauguins / from his second trip to Tahiti”; noting how, at a Hindu wedding, “the bride’s mother gives the groom a coconut”; and celebrating odor in “Ode to Words for Smells,” and noise in “Ode to Words for Sound.”

This section of odes also contains “Ode on Killing Sadness,” which I found deeply moving in its description of the narrator visiting women in a nursing home in Havana, while missing her own mother and feeling some regret as a daughter:

because I still miss her so much

after five years, and I kiss the Cuban woman’s cheek

and I want to take her home with me

but we don’t even speak the same language,

which you could have said about me

and my own mother, and all these women in Havana

have raised better daughters than I was

Holoholo is composed of many correlating parts that don’t settle on a particular theme or message. Part romp, part wisdom, there is more than enough in here to spark sadness, joy, regret, side-eye, and laughter in any reader.”

Barbara Hamby’s Holoholo, Reviewed by Lee Rossi

“How to describe a book as filled with delights as Barbara Hamby’s Holoholo. Ostensibly a book of odes, these are not just poems of praise; she urges her readers to construe the term “ode” in the widest possible sense: as a “poetic stance, a poetic investigation of what it means to be a human being at any moment in time.”

Keats, of course, is one of her many co-conspirators in this late night jam, and indeed in “Ode on My Nightingale” her “little god” [the nightingale] tells us, “I am the cosmologist / of the atomic, high priest of everything / you never wanted to be . . . / your drinking water straight from the stream, / . . . I am the derivative of sin. O let me in.” The struggle is on for the soul of this poor soul, and only when everything in the cosmos (and the dictionary) is let in will she be at peace.

This openness to experience is replicated in the expansive syntax of these poems. One finds oneself wandering her sentences like Dante on his way to Heaven. In “Ode on Following My Mind,” we escort the poet not only through her waking but also her dreaming life, where she tours the Paris of her brain, “the Arc de Poésie and the Bistro de Chekhov / and the Jardin de Procrastibaking,” only to realize:

… when you’re born, your brain is medieval Paris

and then Baron Haussmann begins to build your celestial

cranial city with its Place de la Concorde,

which took years of meditation to clear, bulldozing the hovels

of your parent’s Baptist bugaloos …

“Holoholo” is a Hawaiian word that means “walking out with no destination in mind,” and these poems allow themselves that kind of freedom, a freedom which embraces the infinite variety of human experience, and language. I’m particularly fond of her “Ode to Yiddish.” She’s grateful, she tells us,

to my former boyfriend for the Yiddish that I pepper

my conversation with, and sometimes I get all

ver klempt and schmaltzy about those years we spent

in our vegetarian squalor …

But then she remembers the fights. Such fights they had!

… I thought he was schmendrik,

and he hated all my tchatchkes, and I couldn’t stand

his constant kvetching and he hated how big my tuches

was …

but now that he’s an alter cocker and I’m a bubbe, time

has erased so many of my grievances,

so I say shalom, old friend, time is a gonif, but sometimes

he steals the dreck we never needed anyway.

If we say the title of Hamby’s book a few times to ourselves (like a mantra), we realize that, in fact, it’s an echo: holo / holo. And we know that a mirror is a visual echo. So, on one hand, these are poems that mirror the poet’s world—America / herself / her wanderings—but is that all they strive for? Every encounter with reality is re-formed or enlivened by something we might call inspiration. “Inspire” comes from the Latin word to breathe, and we’ve already noted the breathiness of these poems, a breathiness which is Whitmanic (emphasis on the manic) out of Charles Olson and the Beats. Sentences run on and on, sometimes the length of these lengthy poems, but often at least 4 or 5 strophes.

Keats is here, and Whitman. And also the Emily Dickinson who wrote, “I am out with lanterns, looking for myself.” The search is on. Who is this poet? Who does she speak to? And to what end?

Hamby’s previous book Bird Odyssey wrestled with what it means (in our numbingly patriarchal culture) to be a woman, especially a woman writer. This volume too engages daddies big and small, whose lives and lifestyles depend on exploiting women and others. In “Ode to Driving on Venice Boulevard with Emily Dickinson,” she asks, “how does any woman become herself in this crazy world?” But it’s not just the world which frustrates a woman’s becoming herself; women too are “at war with their bodies and every missile / thrown from their own minds into the hurricane of their hearts.”

In “Ode on Going Holoholo and Getting Lost” she offers a prayer, for freedom and renewal:

… O let me always be lost in this storm of time,

may I turn every corner and see something I’ve never seen before,

see the world to me like a dragon with a mouth full

of torch ginger or a peony with a head of a thousand petals,

her pink shores and armada of clouds, each galleon

carrying all the gold of the summer when I was twelve,

the shimmer-slicked mornings and my salt-wracked breath.

So what, she declares, if this freedom is mostly imaginary; whether you’re twelve or a poet, summer is all the gold you need.

But maybe there are other answers. For this poet, no options are foreclosed. What about revolution? (Is it REAL, or is it METAPHOR; only the poet knows.) Consider “Ode on Fire,” in which she pictures herself as a clandestine revolutionary: “the cigarette girl with the bazooka of annihilation” “handing cigars to Big Daddys at the Tropicana while revolution / sneaks into Havana.”

Such riches in the language: the “bazooka of annihilation” reminding me of Ginsberg’s “hydrogen jukebox,” the rhyming (Tropicana / Havana), and that wonderful pun—not only is the poem about fire, but the poet sets herself as on fire: “with Jehovah, with Mohammed / with night bombing drones over Syria.” Re-tooling the tools that the culture gives her (“our word hoard, our dictionary / of love and conflagration, our bible of fallen walls and trumpets, / … setting myself on fire with nickel bags of hooey,” like some Vietnamese Buddhist), Hamby offers her readers a beacon in this darkening world.”

Ashville Poetry Review:

Are You an Addonizio or a Hamby?: A Review of Kim Addonizio’s Now We’re Getting Somewhere and Barbara Hamby’s Holoholo by Suzanne Cleary

Addonizio, Kim. Now We’re Getting Somewhere. New York, NY: W.W. Norton and Company, 2021. ISBN 978-0-393-54089-5. $26.95. 85 pages.

Hamby, Barbara. Holoholo. Pittsburgh, PA: U of Pittsburgh Press, 2021.

ISBN 13:978-0-8229-6658-6. $17.00. 85 pages.

I.

Fiction Workshop was a place of harsh criticism and tears. We’d hear about it, afterward. By contrast, our Poetry Workshop, taught by the delightful and brilliant Donald Finkel, was a lifeboat bobbing at the edges of the choppy water that is a brand new MFA in Creative Writing program (Washington University, 1977). So it is no surprise that I vividly remember the day that Don casually pushed his chair back, rested a knee on the edge of the conference room table, and let us have at it.

It was a poem that I admit I hardly remember. I think that it was a narrative lyric that lacked clarity. The ten of us divided roughly down the middle: the poem told too much, the poem did not tell enough. We sat on the edge of our chairs, progressively raising our voices. Someone actually pounded a fist on the table, which probably is when Don pulled his chair closer, leaned in. He spoke very softly, In the end, the best version of this poem may be the one that most corresponds to your own taste. It’s all a matter of taste. Your taste. I felt my body relax, joining my classmates in a collective sigh. Then, with famously well-honed timing, Don added, But the thing is, you want to have good taste.

II.

Kim Addonizio’s Now We’re Getting Somewhere and Barbara Hamby’s Holoholo are strong collections by two highly accomplished poets. Each book is the poet’s eighth, in a long line of well-respected volumes. Each book is primarily lyric narrative, spoken by a first-person narrator who bears strong resemblance to the poet herself. Both reference contemporary and pop culture, both employ humor and sense detail galore. Yet Addonizio and Hamby are very different poets, each having crafted a distinctive speaker/persona. I strongly suspect that these books will appeal to two distinct audiences—that is, to readers with widely divergent taste.

By taste I mean simply that readers want different things from a poem; without these, we feel cheated, or at least dissatisfied. Taste may be an inclination toward a particular subject matter, or form, or tone. It may be a preference for lyric or for narrative, for traditional or experimental. Some read to feel, others read to think. As readers, we may self-identify as Dickinsonians versus Whitmanians, or identify ourselves as among one of the indispensable camps that argue for more categories, while also observing that none of these aforementioned categories are mutually exclusive. If we are serious readers of poetry, or serious poets, we strive to broaden our taste, even as we own up to having one.

III.

Kim Addonizio’s Now We’re Getting Somewhere is divided into four sections: “Night in the Castle,” “Songs for Sad Girls,” “Confessional Poetry,” and “Archive of Recent Uncomfortable Emotions.” These subjects would not have been out of place in her justifiably acclaimed 1994 debut, The Philosopher’s Club, but this new book ably demonstrates how far this poet’s work, over the years, has developed and deepened.

The book takes its title from the poem “Small Talk,” which begins, “Let’s skip it and get straight to the rabid dog at hand./There is some weather we’re cowering from.” The voice is quintessentially Addonizio: direct, directive, confrontational. In two six-line stanzas, the speaker belittles the concept and practice of small talk, which she regards as a waste of time, precious time being one of Addonizio’s keenest themes. “Small Talk” ends with these lines: “Everything you say is tiresome./I’m going to walk away slowly and not look back./Now we’re getting somewhere.” The message is searing, as is the craft: the push/pull from you to I, the commandeering we’re, the tension of the short declarative statements. The final line fairly spits with challenge.

Still, some readers will wish that the poem did not end here, that the poet would explore this somewhere. Frustrated, they might ask, Where, exactly, are we getting? But Addonizio knows exactly what she is doing. She has crafted this moment so that the reader has no recourse but to feel the discomfort of this challenge. Addonizio’s central poetic project is to propel the reader into emotional discomfort and, pointedly, refuse to defuse it. She will not weaken emotional intensity with cerebration. Feel it, the prototypical Addonizio poem would say. I didn’t create our cracked-up world, but I am determined that you—and I—feel it.

Kim Addonizio can be seen as a poet of traditional Romantic temperament in that she prizes emotion and the individual, the colloquial and commonplace over the high-flown; she displays a tendency to (winningly) self-dramatize. Her poem “Still Time” is about visiting the room in which John Keats died. It is difficult for me not to quote this entire poem, rich as it is in observation and insight. It is Addonizio at her best: the voice both gorgeous and coarse, both dreamy and get-real. It begins, “in Severn’s letters Keats is still alive, though coughing blood,” easing the reader into the tragic, familiar story. A few lines later we read, “In books you fall in love with, you always slow down/a few pages before the end but then there you are/with only the back-cover blurbs that say/This story will make you cry and maybe an outdated photo.” Now we’re getting somewhere, indeed, somewhere considerably closer to the bone, our own mortality pointedly present.

Here are the final lines: “[Y]ou can climb the stairs to that room in Rome/and see the flowers on the ceiling, the same ones Keats held/for weeks in his fevered gaze. That’s as close as you can get./Go home. Your miserable bitch of a neighbor is gone,/carried out and never to return.” Only this poet could have made that jump to the bitch of a neighbor. The lines jolt us with reality in the form of a trying domestic trial, lines delivered bluntly and unapologetically, with a distinctive biting humor comprised of equal parts resignation and determination.

Addonizio made this trip to Rome while on a writing fellowship. Throughout this collection, she acknowledges the privilege of her life, with regard to both social class and race. Humor delivers some of her most scathing observations, especially with regard to the dangerous and enduring glamour of drinking and drugs. “Resume” (“after Dorothy Parker”) reads in its entirety: “Families shame you;/Rehab’s a scam;/Lovers drain you/And don’t give a damn./Friends are distracted;/Ageing stinks;/You’ll soon be subtracted;/You might as well drink.” One of the enduring images of Now We’re Getting Somewhere appears in “Happiness Report,” which begins, “I was happy when I was drunk one night in 1985/squatting in the already pee-wet grass next to Jill Somebody/outside the graduate student poetry reading….”

In the taste categories, you are either an Addonizio or a Hamby.

IV.

Barbara Hamby, born and raised in Hawaii, prefaces Holoholo by defining this word as the Hawaiian expression for “walking out with no destination in mind.” This word also identifies Hamby’s poetic strategy. Her primarily narrative poems begin with a particular scene or situation, and from there set out for adventure, discovering other places, stories, observations, and insights. Holoholo is divided into three sections: “Americanski Odes,” “Ontological Odes,” and “My Holoholo Odes.” Endnotes provide a history of the ode, defining it as a praise poem, and also provide a brief history of Hamby’s long fascination with this form.

The title of this book comes most directly from the poem “Ode on Going Holoholo and Getting Lost.” The opening lines are “A hurricane is bearing down, the red eye swirling in the Caribbean/like a rotating substation of Hell, gathering its evil mojo/into a cauldron of wind and heat, and we’re boarding up our windows,/filling the tub with water, counting out cans of tuna and soup…” The holoholo that is this poem leads to memory (“and I think of how much I love to get lost, going/ holoholo in Venice”), to prayer (“O let me always be lost in this storm of time”), and eventually ends with an early memory (“all the gold of the summer when I was twelve,/the shimmer-slicked mornings and my salt-wracked breath.”) As in nearly all of her poems, Hamby paints a dynamic, rich portrait of a physically rapturous world. She shares Addonizio’s sensual acuity, and a romantic’s keen interest in time.

Barbara Hamby’s central poetic project is to use physical rapture as a springboard for thought. An essentially cerebral poet, she paints rich, characteristically fond, portraits of cities, vistas, people, and food, but she is equally fascinated by the unseen dimensions thereof. Her long-lined poems welcome history, philosophy, aesthetics, literature, etymology. They name-drop like crazy, with humility and good humor.

Hamby writes expansive poems about a world much larger than herself. For example, “Ode on Killing Sadness”—killing functions as both verb and adjective—tells the story of a dead woman buried with her dead baby between her legs, the grave later opened to reveal the child cradled in the woman’s arms. Holoholo leads to “I say a prayer/ for my mother, whose hard kisses were so sweet/and I ask her to let me tell her story/as I know it.”

“Ode on My Mother’s Lingo” is a love poem to language as well as to the poet’s mother, and includes the effusive yet utterly convincing statement, “O word crushes, how you make my heart flutter,” and the joyous list “laggards, lollygaggers, pettifoggers, miscreants, and prevaricators.” Holoholo leads to the humbly presented confession, “now that I am free from her eye,/I want it back, not because I think she was right, but because she loved/me so much I took that love as my due.” This moving admission is not the end of the poem. Hamby, as usual, has more to say. Hamby exuberantly explores that “somewhere” where we are “getting.”

“Ode to the Sacred Heart of Everyone, Including You and You and You” is a prime example of Hamby’s humor, sometimes critical but never caustic. The poem explores Catholic iconography, opening, “Hey, Catholics, what is it with that red heart out there/beating on Jesus’ chest like some Frankenstein/experiment gone bad…” Holoholo leads as if inevitably to “wearing your heart on your sleeve…/like when you are twenty and have given/your heart to a moron and expect him to be Einstein,/well, not him, but a little smarter than average,/and he is not.” Later we read, “but wait, I just saw/Mary with a crown and six or seven swords piercing/her bosom, and that’s got to hurt, plus all the mess…” Some readers will wish that this poem were less messy, tidier in focus and verbiage. Why? Beats me.

V.

Hamby’s poem “Ode on Gaugin, Russia, Arles, and Consciousness” is another rollicking meditation, this one on artistic inspiration. It explores Gaugin’s need to find a place that would inspire him, as Arles had inspired Van Gogh. She writes, “he [Gaugin] had to go half-way around the world to find his/ own Arles because there are some rooms that speak/ to us and others that do not.” This seems to me as good a definition as any of taste. Some things speak to us, and others don’t.

Categorizing taste reminds me a bit of the quizzes that used to appear in teen magazines, and today can be found all over the Internet. The quiz presents a series of multiple-choice questions such that your answers identify you as, say, a John Lennon fan versus a Ringo Starr fan. Addonizio and Hamby, senior poets still in their prime, are of the demographic that would remember that quiz, so I am emboldened to ask, Are you an Addonizio or a Hamby?

If you are a serious reader of contemporary American poetry, you are both.

Suzanne Cleary